Rajasthan’s Art Heritage: From Walls to Worldwide Fame

Rajasthan’s Art Heritage: From Walls to Worldwide Fame

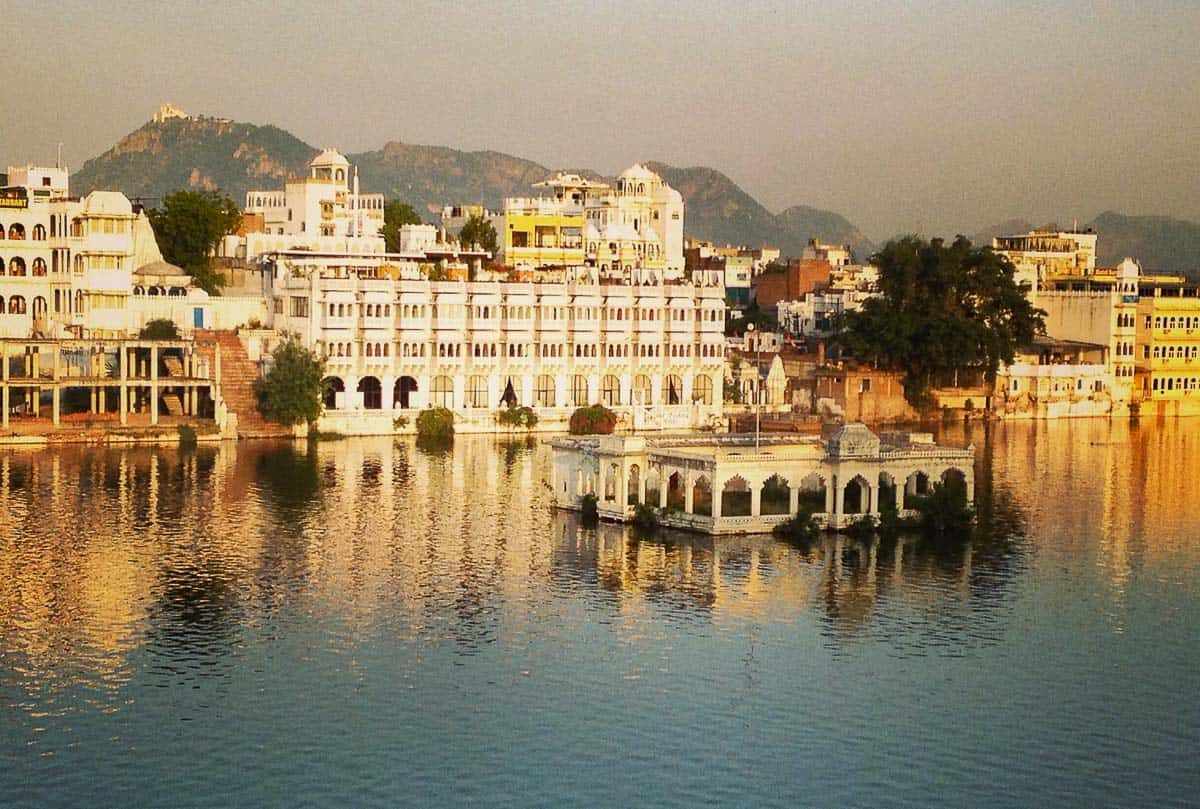

Rajasthan’s art is a visual documentation of its cultural and historical evolution. From the fort walls of Amer to the intricately painted havelis of Shekhawati, the art found across this Indian state reveals more than just decorative skills. It offers insight into traditions, beliefs, and local life that have been passed down for generations. This article explores how the traditional art forms of Rajasthan transitioned from local storytelling mediums to being appreciated on international platforms.

What Were the Origins of Rajasthani Wall Art?

The origins of Rajasthani art lie in its early mural traditions, where artisans painted on walls, ceilings, and temples using natural pigments. These murals often depicted mythological tales, royal events, and elements from everyday village life. The frescoes of Bundi and the elaborate paintings of Shekhawati’s havelis serve as early evidence of this heritage. Such paintings were more than mere ornamentation; they were communicative tools for religious, cultural, and historical narratives.

Over centuries, these wall paintings evolved in style and scope. While retaining regional characteristics, they gradually adapted to the materials, spaces, and patrons available at the time. The artisans’ ability to blend visual storytelling with architectural elements marked a foundational phase in Rajasthan’s art legacy.

How Did Artistic Styles Vary Across Regions?

Rajasthan, though unified under a single cultural umbrella, is a land of diverse regions, each nurturing distinct artistic identities. In Mewar, the style leaned toward devotional paintings, especially those focused on Lord Krishna. Marwar developed a more robust, earthy style with bold lines and vibrant palettes. The Shekhawati region became known for its extensive frescoes that adorned merchant mansions, often illustrating scenes from mythology, history, and even colonial interactions.

Bikaner, on the other hand, was influenced by Mughal techniques, incorporating more refined strokes and detailed floral patterns. This regional diversity allowed for a wide range of interpretations of similar themes, enriching Rajasthan’s overall artistic tradition.

What Role Did Folk Artists Play in Shaping This Heritage?

Professional artisans and court painters had their own space in Rajasthan’s art scene, but folk artists were equally influential. These artists, often self-taught or trained through apprenticeships within families, played a crucial role in keeping traditions alive outside palaces and temples.

Folk artists typically painted for community rituals, storytelling sessions, or religious festivities. Their works were created on temporary surfaces—walls, cloth scrolls, or wooden panels—and often disappeared over time, making their preservation more challenging.

An exceptional example is Kaavad Art, where wooden shrine-boxes are painted with episodic panels. These are used by storytellers, who narrate spiritual and heroic tales by unfolding the panels one by one. This art form represents the integration of function and creativity, passed down orally and visually within specific artisan communities.

What Are the Key Themes and Symbols in Rajasthani Art?

Traditional Rajasthani art frequently revolves around themes of devotion, folklore, nature, and royal life. Lord Krishna, in his various forms, is one of the most frequently depicted figures, especially in Mewar-style paintings. Other common themes include scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, village activities, royal processions, and hunting scenes.

Nature also plays an essential role. Birds, animals, trees, and water bodies are not just background fillers but carry symbolic meanings. For instance, the peacock often represents love and monsoon, while elephants signify strength and nobility. Artworks like Bird on Canvas capture these elements vividly, using fine lines and regional detailing to narrate layered stories.

These symbols serve both artistic and philosophical functions, connecting viewers with deeper cultural meanings embedded in visual simplicity.

How Did Portability Affect the Spread of Rajasthani Art?

The transformation of Rajasthani art from wall-bound to portable formats played a significant role in its wider dissemination. Artists began to create on fabric, paper, and wood—materials that could travel easily beyond the state’s borders. These portable artworks allowed collectors, traders, and pilgrims to carry a piece of the culture with them, indirectly promoting Rajasthan’s visual identity across regions.

The development of scroll painting traditions, such as Phad painting, reflects this portability. In this form, long horizontal cloth scrolls are painted with episodes from heroic ballads. These are then used by traditional singer-narrators to perform stories during village gatherings. Today, viewers can also experience these works through Phad Painting Online, which offers a window into this dynamic art form’s intricacies and cultural context.

How Has Global Interest Influenced Traditional Practices?

Global interest in Rajasthani art has increased significantly in the last few decades. Exhibitions, academic research, and tourism have brought attention to these forms, resulting in both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, international exposure has led to economic benefits and a revival of some fading traditions. On the other hand, this has also raised concerns about the commodification and loss of original context.

To meet external demands, some artists adapt their work for contemporary tastes—changing scale, colour palettes, or subject matter. While this allows traditional forms to survive in new formats, it also risks altering the original intentions and meanings.

Thus, maintaining a balance between preservation and innovation remains essential for cultural sustainability. Many artisan families continue to produce artworks in their authentic forms, ensuring that while the audience may change, the core values remain intact.

What Is the Role of Documentation and Education?

Preservation of any cultural heritage requires active documentation and educational outreach. Institutions and independent researchers have taken significant steps to archive and analyse Rajasthani art forms. Digital platforms have further facilitated this by enabling audio-visual documentation, online exhibitions, and artist interviews.

Workshops, community art projects, and school programs have started including elements of folk and traditional art in their curriculum. This promotes early exposure and appreciation among younger generations.

Efforts are also being made to translate oral traditions into written formats and catalogues, ensuring that the intangible elements of Rajasthan’s art are not lost with the passing of generations.

How Do Artists Navigate Tradition and Modernity Today?

Modern-day Rajasthani artists often walk a fine line between maintaining tradition and embracing innovation. Some stay deeply rooted in classical methods, following family or community techniques with minimal changes. Others use traditional motifs but experiment with modern materials or presentation styles to engage with new audiences.

For instance, one may find miniature painting techniques applied to contemporary subjects, or folk themes represented in graphic prints. These changes reflect a living tradition that evolves with time while staying connected to its roots.

There is also a noticeable trend of collaboration between traditional artists and designers, aiming to integrate folk aesthetics into urban contexts without erasing their origin stories.

What Makes Rajasthan’s Art Heritage Stand Out Globally?

Rajasthan’s art heritage stands out for several reasons. First, its strong narrative component sets it apart from purely decorative art traditions. Second, the diversity in styles across different regions of the state enriches its overall visual language. Third, the integration of religious, cultural, and ecological elements adds layers of meaning to even the simplest motifs.

Moreover, the art is often participatory. It’s not created in isolation but in the context of festivals, rituals, or storytelling sessions, giving it a communal character. This social function, coupled with visual elegance, makes it relevant even in global artistic conversations.

Whether in museum galleries, academic journals, or personal collections, Rajasthan’s art continues to attract attention because it reflects a deep engagement with life’s moral, spiritual, and aesthetic dimensions.